Ask most people: does the First Amendment protect LIES?

All, or nearly all, will give the same answer – No way! Of course not! Lies are not protected speech! DUH!

If that’s what you think, congratulations – you just failed First Amendment law 101. But don’t feel too bad. You have LOTS of company, including some judges. I’ve personally stood in front judges who said some version of the same thing: “The First Amendment does not protect lies.”

Each time I’ve heard that, I stop, take a deep breath, and remember – lawyers are called “counselors” because our job is to help judges understand the law so they can reach the right legal conclusions. We are literally there to counsel the court about what we think the law is. Because being a judge is HARD. Judges are not experts in every tiny aspect of the law. That’s why we are there to help them.

So let me tell you – does the First Amendment protect FALSE statements? Answer – absolutely YES, with a few exceptions.

I could write an entire textbook on this topic, but let’s just start with a couple of helpful cases.

Hustler v. Falwell

The first is a case we learned about in ConLaw – Hustler Magazine v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988) (see also: Wikipedia’s helpful discussion). Bear in mind – I started law school in 1997, so this case was less than 10 years old at the time.

If you’ve never heard of this case, the facts are hilarious. Back in the early 1980s, Hustler was a porn magazine that was a raunchier version of Playboy. The founder, Larry Flynt, was a colorful character who liked to mix political commentary with porn.

At that time, some religious leaders were vehemently opposed to porn. One of the most vocal critics was a famous TV preacher named Jerry Falwell. He actively attacked Larry Flynt and Hustler and urged people to boycott the magazine.

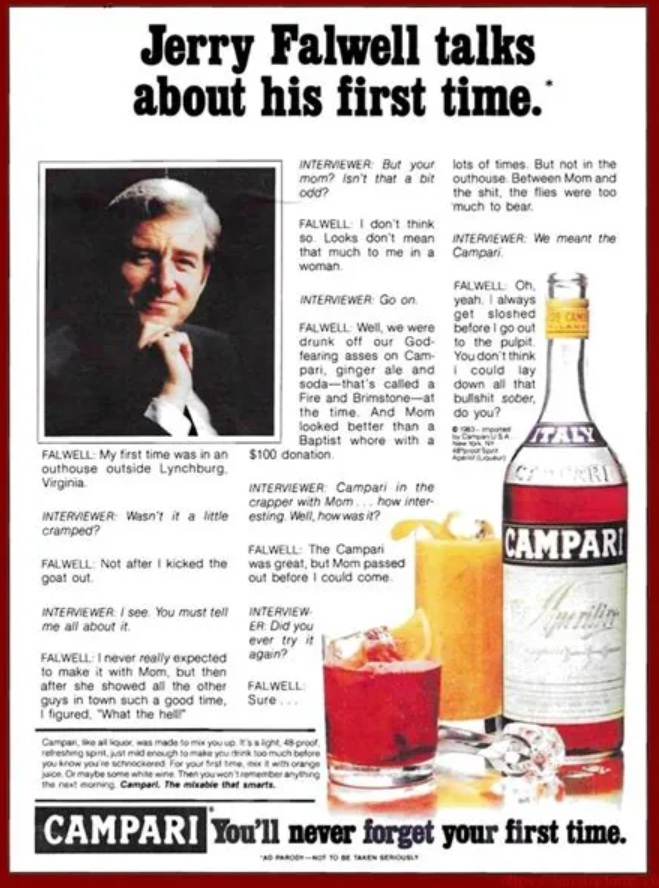

In response, Larry Flynt ran an “ad” on the inside cover of the November 1983 edition of Hustler. The ad (which was fake) featured Jerry Falwell talking about his “first time”. This was a parody of a well-known advertisement for Campari which featured celebrities talking about their “first time” (meaning the first time they drank Campari, but also with some sexual innuendo).

In this ad, Jerry Falwell is quoted as describing the first time he had sex. The ad claimed Jerry had sex with his mother while drunk in an outhouse. BARELY visible at the bottom of the page was this line: “AD PARODY – NOT TO BE TAKEN SERIOUSLY”.

After the ad was published, Jerry Falwell sued Larry Flynt and Hustler for defamation (called “libel” at the time), invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress. Before trial, the judge threw out the invasion of privacy claim, but allowed the jury to consider the defamation and emotional distress claims.

The jury ruled AGAINST Falwell on his defamation claim. The decision was based on the legal rule which (to paraphrase) says a statement can’t be defamatory unless it appears to state “actual facts” about the plaintiff (“actual facts” meaning something that actually happened, not a work of fiction).

By that definition, an obvious joke doesn’t convey actual facts, which is why jokes generally can’t be defamatory.

Although the jury found the ad was not defamatory, it ruled in favor of Falwell on his emotional distress claim. That claim only required proof that the defendant’s conduct was outrageous and upsetting, not that the speech was false. The jury agreed, and awarded Falwell $150,000 in damages.

Larry Flynt appealed to the Fourth Circuit, arguing the Campari ad was protected speech under the First Amendment. He LOST. He then asked the Fourth Amendment for something called “rehearing en banc“. He lost that as well.

The United States Supreme Court took the case, and it unanimously reversed. In short, the Court said the First Amendment protected even hurtful, outrageous speech (even speech like the Campari ad which was literally false, although obviously not intended to be taken as true).

NOTE – technically speaking, the Supreme Court’s decision in Hustler v. Falwell is limited to cases involving a “public figure plaintiff” (because Jerry Falwell was extremely famous). It left open the question of whether the First Amendment would protect a similar attack against a private (non-famous) plaintiff.

This distinction is important because the Supreme Court has always extended more protection to speech when the plaintiff is famous, or when the speech involves a public issue or a matter of public concern. See Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011) (holding First Amendment barred emotional distress claim brought by a private figure plaintiff because the actionable speech involved a matter of public concern).

On the other hand, when the plaintiff is not a public figure, and the speech does not involve a matter of widespread public interest, the Court has generally agreed the First Amendment protection is lower (but to my knowledge, the Court has never specifically explained the amount of protection which applies in an emotional distress case involving a private figure plaintiff where the speech was not a matter of public interest).

Anyway, the Hustler case was such a big deal, they turned it into a movie (which is OLD, but GREAT). If you’ve never seen it, please watch this clip depicting the oral argument before the Supreme Court. I have argued many appeals, and I often watch this clip the night before to get my head focused. It also has some extremely important commentary about the First Amendment, and why it applies even in extreme circumstances.

To be fair, Hustler did not literally say the First Amendment protects the right to LIE. It says the First Amendment protects false statements which reasonable people would NOT think were meant to be taken as true (i.e., jokes about having sex with your mother in an outhouse).

United States v. Alvarez

So let’s look at one other case – United States v. Alvarez, 567 U.S. 709 (2012) – where the Supreme Court said EXACTLY that – the First Amendment protects the right to LIE.

I personally think the facts of Alvarez are outrageous. This was a criminal case where the defendant was elected to a local water district board. During his first public meeting, the defendant (Mr. Alvarez) introduced himself with this bullshit: “I’m a retired marine of 25 years. I retired in the year 2001. Back in 1987, I was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. I got wounded many times by the same guy.”

If you don’t know – the Congressional Medal of Honor (a/k/a the “Medal of Honor”) is the highest military award you can get. It is reserved for people who have displayed extraordinary bravery and valor serving their country. It is a BIG deal.

It turns out, Mr. Alvarez lied. He lied about being a Marine. He lied about being injured in battle. And he lied about receiving the Medal of Honor. According to the Supreme Court decision, this was a common practice for Mr. Alvarez: “Lying was his habit. Xavier Alvarez, the respondent here, lied when he said that he played hockey for the Detroit Red Wings and that he once married a starlet from Mexico.” 567 U.S. at 713.

After lying about his military service, Alvarez was charged with a criminal violation of the Stolen Valor Act which made it a federal crime to lie about receiving military honors. In response, Alvarez argued the First Amendment protected his right to lie.

Kind of surprisingly, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed – lying IS protected speech.

To paraphrase, the Court held (as a general rule) that ALL speech is protected by the First Amendment, EXCEPT for a few narrow categories which the Court listed:

- Advocacy intended, and likely, to incite imminent lawless action, see Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 (1969) (per curiam);

- Obscenity, see, e.g., Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973);

- Defamation, see, e.g., New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) (providing substantial protection for speech about public figures); Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc., 418 U.S. 323 (1974) (imposing some limits on liability for defaming a private figure);

- Speech integral to criminal conduct, see, e.g., Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co., 336 U.S. 490 (1949);

- “Fighting words,” see Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942);

- Child pornography, see New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747 (1982);

- Fraud [referring to the financial/commercial type], see Virginia Bd. of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc., 425 U.S. 748, 771 (1976);

- True threats, see Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705 (1969) (per curiam); and

- Speech presenting some grave and imminent threat the government has the power to prevent, see Near v. Minnesota ex rel. Olson, 283 U.S. 697, 716 (1931).

After reviewing this list of traditionally unprotected speech, the Court found lying about military honors (as disgusting as it is) was not on the list. Therefore, the Court held the First Amendment protected Mr. Alvarez’ right to lie.

In its analysis, the Court made it CRYSTAL clear — all speech, even knowingly false speech, IS protected, unless it falls within the list of above stuff (and NOTE – you can’t just use a generic label like “fraud” to take speech outside the First Amendment; clearly, Mr Alvarez engaged in a type of “fraud” when he lied to the public about his military service, but he didn’t do this to gain money or something else of value, therefore his conduct didn’t fall outside the First Amendment):

Absent from those few categories where the law allows content-based regulation of speech is any general exception to the First Amendment for false statements. This comports with the common understanding that some false statements are inevitable if there is to be an open and vigorous expression of views in public and private conversation, expression the First Amendment seeks to guarantee.

The Government disagrees with this proposition. It cites language from some of this Court’s precedents to support its contention that false statements have no value and hence no First Amendment protection. These isolated statements in some earlier decisions do not support the Government’s submission that false statements, as a general rule, are beyond constitutional protection. [citations]

In those decisions the falsity of the speech at issue was not irrelevant to our analysis, but neither was it determinative. The Court has never endorsed the categorical rule the Government advances: that false statements receive no First Amendment protection.

567 U.S. at 717 (emphasis added) (cleaned up).

In theory, this makes sense. Donald Trump has famously lied about his weight; claiming to be 225 lbs. If Trump lied about his weight, should that be a crime?

Thankfully, Alvarez says no. People are allowed to lie in most aspects of their lives. I don’t endorse that, but that’s the law.

In closing, the Supreme Court agreed the First Amendment protected Mr. Alvarez’ right to lie about his military service:

The Nation well knows that one of the costs of the First Amendment is that it protects the speech we detest as well as the speech we embrace. Though few might find respondent’s statements anything but contemptible, his right to make those statements is protected by the Constitution’s guarantee of freedom of speech and expression. The Stolen Valor Act infringes upon speech protected by the First Amendment.

Id. at 729-30.

While I normally NEVER cite concurrences, these comments from the concurring opinion of Justice Breyer are also helpful:

False factual statements can serve useful human objectives, for example: in social contexts, where they may prevent embarrassment, protect privacy, shield a person from prejudice, provide the sick with comfort, or preserve a child’s innocence; in public contexts, where they may stop a panic or otherwise preserve calm in the face of danger; and even in technical, philosophical, and scientific contexts, where (as Socrates’ methods suggest) examination of a false statement (even if made deliberately to mislead) can promote a form of thought that ultimately helps realize the truth.

Id. at 734.

Oh, I know — Alvarez doesn’t apply to lawyers, right? I don’t read it that way. I see nothing in the decision that limits the scope of the rule it described. Of course, that doesn’t mean the First Amendment gives lawyers the right to ignore any/all laws and rules. There are certainly times when the First Amendment must yield to permit a court to protect against “some grave and imminent threat the government has the power to prevent”. I have no issue with that.

Still, as a general rule, Hustler and Alvarez make it clear – the First Amendment generally DOES protect a person’s right to lie in many circumstances. I have no intention of invoking that rule in my professional life, but it’s still interesting how many people misunderstand this area of law. Including many judges and lawyers.