Friends,

I was in court this morning. On my way in, a security guy asked the woman behind me: “You here to get married?”

“Yes!”, she happily responded.

Ever the joker, I had to drop this: “I’m here to get divorced! DON’T DO IT GIRL!”

I smiled and explained that was a joke. I told her I was a lawyer and I congratulated her on getting married.

The security guy (who was bald and probably 65) heard all this. He then looked at me and said: “I used to be a lawyer. 20 years. I got out and never looked back.” We shared a couple quick stories, and I moved along.

The exchange got me thinking about how people enter and leave the practice of law. Leaving is pretty easy. I know many former/recovering lawyers. I’m about to be one of them.

But this reminded me — getting INTO law is HARD. First there’s the test to get into law school (the LSAT). Once you’re in, lots of studying/work. Then there’s the bar exam, the ethics exam (MPRE), and of course the background check (called “character & fitness”). Plus, a law degree can be crazy expensive — way over $100,000 (and often closer to $200,000) for tuition, books, rent, plus three years of lost income.

Once you graduate, then the really hard work starts – trying to learn the practice of law. You have basic general background info from school, but new law grads are not even remotely ready to handle cases on their own. Mastering the rules, procedures, and local practices is a MASSIVE task. It took me easily 10 years before I was comfortable handing cases from Day 1 to final judgment.

Along the way, I got lots of help from older lawyers. Many people don’t know this, but there is a strong tradition in our profession for older attorneys to help younger folks learn the trade. Mentoring is common, and badly needed.

As I am about to exit the practice of law, I wanted to share some pearls of knowledge I’ve picked up along the way. I intend this to be purely educational. The goal is to help people learn the right way to do things….which will include showing them the wrong way.

As my first entry in this series, I want to talk about the first thing most lawyers file — a Notice of Appearance.

I Appear, Therefore I Am

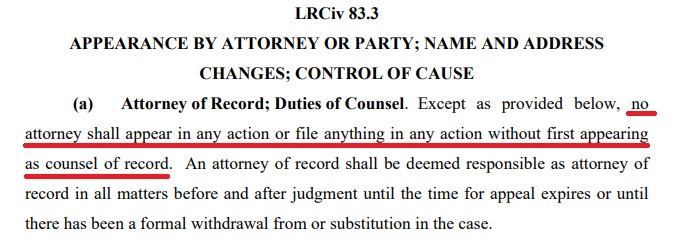

This may seem beyond obvious, but when you want to represent a client in a case, you first need to “appear” for that client. Why? Because the rules say so. Every court is different, but in federal court in Arizona, Local Rule LRCiv 83.3 says a lawyer cannot file anything in a case unless they have formally appeared.

This may be hard to believe, but I’ve had cases where lawyers tried to slide into the case without first appearing. For instance, maybe you are in court to argue an important motion. Rather than the opposing counsel you know, a stranger shows up and tries to argue the other side. Sure, they might be a lawyer, but you have no clue who they are (and neither does the judge). This is weird and can be uncomfortable.

To prevent discomfort, courts generally require you to file a written Notice of Appearance as the first thing you do. It’s required, so don’t even think about diving into a new case until you formally appear. It’s just a one-page thing, so do it. ALWAYS. IMMEDIATELY.

Sorry Client, It’s Over; I’m Out.

But what about withdrawing? When things go south and you need to leave, is getting out as easy as getting in?

Not always. It shouldn’t be hard, but for some unknown reason, this is a mistake many noob lawyers make…and it’s totally inexcusable.

The #1 most important thing to know is this — when you move to withdraw in the State of Arizona (or California), you must be extremely limited in what you say. Don’t got into detail. AT ALL. EVER.

This is not just smart. It is literally an ethical requirement, and it can be malpractice depending on how badly you screw it up. So don’t screw it up.

Here’s the problem — let’s say you have a client who is very difficult. Imagine the client has failed to pay you for months. The client also lied to you or is otherwise guilty of bad conduct. They asked you for advice about how to murder someone and get away with it. You just don’t feel right helping them anymore.

When you move to withdraw, can you tell the judge: “Help! Please let me withdraw because my client is a broke psycho and I just can’t deal with this madness anymore!”

NO, you cannot do that.

The reason (in both Arizona and California) is an ethical rule called ER 1.6. I have written about this rule before. See The Arizona Bar’s Odd (& Incorrect) Obsession With ER 1.6.

In Arizona, the State Bar views ER 1.6 as an extreme and unlimited restriction which limits a lawyer’s ability to say anything without client consent. In Arizona, the Bar believes ER 1.6 prohibits a lawyer from even mentioning the client’s name (or any other detail about their case) unless you have consent. I don’t agree with this view, but that’s how Arizona sees it.

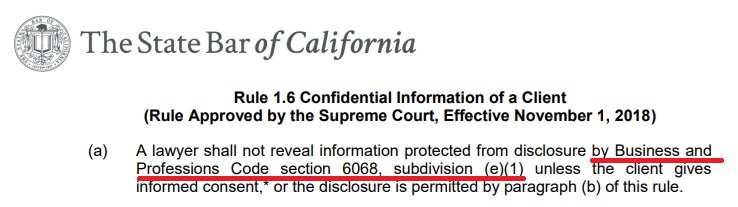

California is FAR more chillaxed with this stuff. California has essentially the same rule as Arizona, but the wording is totally different:

See https://www.calbar.ca.gov/Portals/0/documents/rules/Rule_1.6-Exec_Summary-Redline.pdf

To recap, Arizona takes the position that ER 1.6 restricts a lawyer’s ability to say ANYTHING about a client without consent. But in California the rule only restricts disclosure of information covered by California Business & Professions Code § 6068(e)(1) which says:

[A lawyer shall] maintain inviolate the confidence, and at every peril to himself or herself to preserve the secrets, of his or her client.

So in California, only client “secrets” are subject to restriction under Rule 1.6, whereas Arizona (incorrectly, in my view) takes the position anything you know about a client is restricted by ER 1.6.

Because of this, Arizona’s position is clear — when a lawyer moves to withdraw, the ONLY thing you are allowed to say is this: “professional considerations require termination of the representation“. That is NOT my view. That is the position of the State Bar of Arizona in Formal Ethics Opinion 09-02. You might have other very good reasons for withdrawing, but you CANNOT go into detail. ER 1.6 absolutely prohibits that.

Now that you know the rule, let’s look at two examples of how a lawyer should withdraw – first the WRONG way, and then the RIGHT way.

Full disclosure – in this example, I am going to use the work of a lawyer named Gregg R. Woodnick as an example. The reason is not a secret. I recently dealt with Gregg in a high profile case, which he “won”. Along the way, Gregg showed himself to be one of the most dishonest, unethical, incompetent lawyers I’ve ever seen.

Those are my subjective opinions, of course. But given that the legal and ethical requirements for withdrawal are clear and unambiguous, let’s take a look at Mr. Woodnick’s work and see how well he did.

How NOT to WithdrawNotice anything wrong here? Rather than complying with the mandatory ethical limit of ER 1.6, Mr. Woodnick went WAAAAY beyond what the rule allowed. Totally off the deep end, and a perfect example of what NEVER to do.

This paragraph is one of the most objectively unethical and incompetent things I’ve seen in a LONG time:

The reason for this motion is that a breakdown in communication between attorney and client has occurred such that the attorney cannot proceed with client’s representation, the client has failed to substantially to fulfill an obligation to the lawyer regarding the lawyer’s services and has been given reasonable warning that the lawyer will withdraw ….

On a scale of A-F, this one is an easy F-. Mr. Woodnick did exactly what the rule forbids — he threw his client under the bus by revealing WAY, WAY too much information (and as the motion notes, it was filed without client consent). When you don’t have consent, you MUST SHUT THE F___ UP (unless you are talking about something that fits in an exception to ER 1.6).

There is no question Mr. Woodnick violated ER 1.6 when he filed this. He basically informed the entire world that: A.) his client was broke and failed to pay him, and B.) there was a “breakdown in communication” (this is common shorthand among lawyers which shows the client wanted to do something against the lawyer’s advice). Both of those things may be true, but under ER 1.6, Mr. Woodnick was forbidden from “revealing” that information without client consent. But he did.

Again, this isn’t even a close call. The State Bar of Arizona’s Formal Ethics Opinion 09-02 makes that crystal clear:

The withdrawing lawyer must protect the client’s interests despite any dispute between the lawyer and the client and despite any wrongdoing of the client. Any disclosures of confidential information must be strictly limited to those circumstances authorized by the Rules of Professional Conduct.

If Mr. Woodnick’s motion is a textbook example of the wrong way to withdraw, let’s take a look at the RIGHT way. This happens to be from a recent California case I handled (and as noted above, the CA version of ER 1.6 is way more lenient). Even though I could have gone into a bit more detail, I decided to play it safe and use the AZ-style method.

As you can see, I went into a fair bit of extra detail to explain the issues to the court. Why did I do that? I did it because California changed its ethical rules in 2018 (to more closely match the modern ABA model rules). Prior to 2018, the ethical rules in California were totally different.

Because of this change, some courts in California still had old local rules which conflicted with the new, 2018 revision to the ethical rules. For example, this specific court (the federal district court in Los Angeles) had a very old local rule which required lawyers to show “good cause” before they could withdraw. That rule directly conflicted with the new 2018 rules in any case where “good cause” was based on secret information protected by Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code. § 6068(e)(1).

For that reason, I took some extra time to make sure the judge understood why I was NOT going into detail about the reasons for my withdrawal. In short, unlike Mr. Woodnick, I understood the ethical implications of revealing client secrets, and unlike Mr. Woodnick, I chose to stay on the correct side of the ethical rule.

27 - Motion to WIthdrawCLOSING THOUGHTS

Look friends – being a lawyer is HARD, but it’s not that hard. Appearing in cases, and withdrawing from cases is something every lawyer does, usually many times. If you want to be a civil litigator, make sure you check the rules, and FOLLOW THEM TO THE LETTER.