You’ve heard of The Bible.

You’ve heard of the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

But have you ever heard of 47 U.S.C. § 230, also known as Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act (the “CDA”)? Probably not.

Unless you are lawyer who regularly practices in the area of Internet Law, you may not know this, but the CDA has been called “The Most Important Law Protecting Internet Speech”and the most valuable law ever written. I’ve even seen people refer to it as the Internet’s “Bible”.

Yeah, the CDA is kind of a big deal.

Although it is not very well known outside the Internet Law community, the CDA benefits and protects virtually every American who uses the Internet (this means YOU). The CDA does this by creating a very simple rule – if a person posts something false on the Internet, the author is legally responsible for his/her words, but no one else is.

So, for example, if I post something false or harmful on Facebook, I can be sued for damages, but Mark Zuckerberg cannot. See, e.g., Klayman v. Zuckerberg, 753 F.3d 1354 (D.C.Cir. 2014). In another example, if I see an interesting article online and I decide to share it with some friends (but the article happens to contain some false or otherwise illegal information), I cannot be sued simply for sharing information that someone else wrote. See, e.g., Directory Assistants, Inc. v. Supermedia, LLC, 884 F.Supp.2d 446 (E.D.Va. 2012).

In a nutshell, the CDA does some very simple things:

- It allows people who are injured by false/defamatory/illegal content to sue the original creator of that content

- As long as you don’t create illegal content, it allows you to freely share information that is already on the Internet without facing liability (i.e., retweeting articles, forwarding links, sharing news stories, etc.)

- It allows websites like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, etc., to host user-submitted content without facing limitless liabilty for illegal content that a user creates

- It protects websites from junk lawsuits seeking to suppress truthful (but unpopular) speech such as consumer reviews

- It allows search engines like Google/Bing to index content making it easier to find, without facing liability

- In short, the CDA allows and encourages the free and open sharing of ideas and information online, while offering no protection to those who create or develop illegal content

Despite all these benefits, the CDA has some haters, many of whom are extremely angry and vocal. Sadly, many of the law’s critics (like Texas senator Ted Cruz) are confused about how the law actually works.

For the most part, anyone who has been criticized online may feel the CDA unfairly limits their ability to seek justice. Remember – if someone tweets something you don’t like, you cannot sue Twitter for “allowing” this (but you can always sue the original author). That rule has proven very frustrating to some people who feel they have been victimized by online speech, and to some extent, their frustration is understandable; the CDA certainly does make it harder (and often impossible) to “shut down” a website simply because it hosts speech that offends someone. That’s great news for website owners and users, but not so great for people offended by something published online.

Having said that, I recently read an article entitled: California Holds That Internet Service Providers, Such As Yelp, Can Disobey Orders To Remove Defamatory Posts – So How Can Companies Remove False Reviews From The Internet?

In this article, the author expressed some harsh views about the CDA, claiming it allows website owners like Yelp to “disobey” court orders directing them to remove false reviews. How outrageous of Yelp, right?! But not so fast…there is more to this story that the author doesn’t tell his readers. With this response, I hope to fix that. This is a little long and technical, so please bear with me.

TRUST ME—I’M AN EXPERT!*

First, let’s get this out of the way – I am a battle-hardened CDA veteran. Over the past 14+ years, I have personally litigated dozens and dozens of CDA cases (I’ll include a partial list at the end), including some fairly major precedent-setting ones that drew national attention. I even had one CDA case that almost made it to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Because of my deep experience in this area, I know the CDA (and the cases interpreting it) extremely well. And since I know this area of law so well, articles that misstate the law or mislead the reader about the CDA really don’t sit well with me. As subtle as it is, the CDA isn’t that complicated, so there is really no excuse for anyone to misunderstand it.

THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT’S DECISION IN HASSELL v. BIRD, 5 Cal. 5th 522 (Cal. 2018)

Let me explain the problem in greater detail.

In his article, Phoenix attorney Kevin Heaphy, discussed a recent case called Hassell v. Bird from the California Supreme Court (which Yelp won, by the way). This case was a big deal among lawyers who regularly practice Internet Law (full disclosure – I was one of many lawyers who filed amicus briefs with the California Supreme Court supporting Yelp’s position).

If you haven’t heard about Hassell, here are the facts — the plaintiff was a California lawyer named Dawn Hassell (what a name; you can’t make this stuff up). Ms. Hassell claimed a former client (Bird) posted a negative review on Yelp that criticized Ms. Hassell and her law firm. Under the CDA, Yelp is not responsible for user-submitted reviews, so Ms. Hassell sued Bird, but she did not include Yelp as a party to the case. Got that? Yelp was NOT A PARTY TO THE CASE. Because it was not a party, Yelp never had any opportunity to investigate or dispute any of Ms. Hassell’s claims and arguments.

The defendant, Bird, did not appear in court (she claimed she wasn’t aware of the lawsuit), so the trial court automatically ruled in favor of Ms. Hassell by default. As part of the final judgment, at Ms. Hassell’s request, the court ordered Yelp (who still wasn’t a party) to remove the review allegedly written by Bird (NOTE – other problems aside, courts normally cannot grant relief against people or companies who are not parties; this simply is not allowed as a matter of fairness and common sense).

After Yelp finally learned of the court order requiring it to remove Bird’s review, Yelp did not simply “ignore” the court’s order. Instead,Yelp went back to the trial court and said: “Hang on just a minute here judge — the law does not allow you to do this.”

Among other reasons, Yelp explained the CDA (a federal law) does not allow courts to enter injunctive relief requiring website operators to remove user-submitted speech. Yelp explained the exact same issue had been raised and considered by several other courts across the country (including other courts in California), and the judicial consensus was basically unanimous – the CDA does not allow the type of relief that Hassell asked for (and got) against Yelp.

Apparently not wanting to look like the bad guy who left Ms. Hassell out in the cold, the trial court judge simply ignored Yelp’s arguments, and the California Court of Appeal did the same. Both courts seemed to take the position that because Ms. Hassell “proved” the Yelp review was false (which really only happened because Bird never showed up), that meant Hassell was entitled to anything she wanted, regardless of whether the law allowed it or not. I’m sorry, but that’s just bad judicial conduct – any judge who puts emotion above the law has no place on the bench.

Thankfully, at Yelp’s request the California Supreme Court agreed to hear the case, and they rejected and reversed the lower court’s position. Instead, the Supreme Court held (as many other courts have) the CDA does not allow injunctive relief against a website owner such as Yelp.

Thus, when viewed correctly, it is simply not accurate to say that Yelp “disobeyed” a court order to remove content. That statement implies (falsely) that the “order” Yelp disobeyed was a valid, lawful order which, in fact, it clearly was not. This should hardly be shocking, but there is nothing wrong with Yelp challenging an illegal court order. If anything, Yelp should be applauded for going out of its way to make sure the law was properly applied and enforced and the lower court’s mistakes were corrected.

The bottom line is this – in Hassell v. Bird the Supreme Court of California agreed (as many other courts already have) that federal law (the CDA) does not permit state courts to order website owners to remove content submitted by third parties — PERIOD. Thus, the court order that Yelp “disobeyed” was actually unlawful, illegal, and improper from the start.

Now, having said all that, in his analysis of Hassell, Mr. Heaphy makes two claims that I take serious issue with.

FAIL #1—THE CDA ONLY LIMITS FINANCIAL/MONETARY LIABILITY, NOT OTHER FORMS OF RELIEF

First, under the heading, “Does a Removal Order Make Yelp ‘Liable’ As a Speaker?” (empahsis added), Mr. Heaphy misstates the legal outcome of Hassell by claiming the California Supreme Court held “an order directing Yelp to remove a defamatory review violated the [CDA] because it imposed liability on Yelp as the speaker.” (empahsis added). By reverse implication, Mr. Heaphy is apparently suggesting that if a plaintiff obtains a court order or injunction that does not impose liability on a website operator such as Yelp, then the CDA would not apply.

NO – WRONG – INCORRECT – FAIL.

Here’s the critically important thing to understand – years ago, people who did not like the CDA began spreading an idea. They argued the CDA only limited claims that sought to impose liability on a website operator. For the purposes of this discussion, the term “liability” means “money” or “money damages”. This argument “sounded good”, so many people began to think it was legally correct (spoiler alter: it’s not).

Under this good-sounding but incorrect theory, if you got a court order or injunction that says a website owner needs to remove content (but the order does NOT say the website owner must also pay money damages), then the CDA is not violated because you are not trying to hold the website owner LIABLE for money damages; you are just trying to make them remove defamatory content which isn’t the same thing as holding them “liable”, thus the CDA doesn’t apply.

That’s the argument Dawn Hassell used in the trial court (which fully agreed with her). It’s the same argument which the California Court of Appeal accepted, and it’s the same argument that I have seen used in many other cases.

But here’s the problem – this argument is 100% DEAD WRONG. It’s not even slightly correct, and anyone who says otherwise is either lying to you, selling something (probably their own services) or they just have no clue what they are talking about.

Since I DO know what I’m taling about, I’ll explain how this really works.

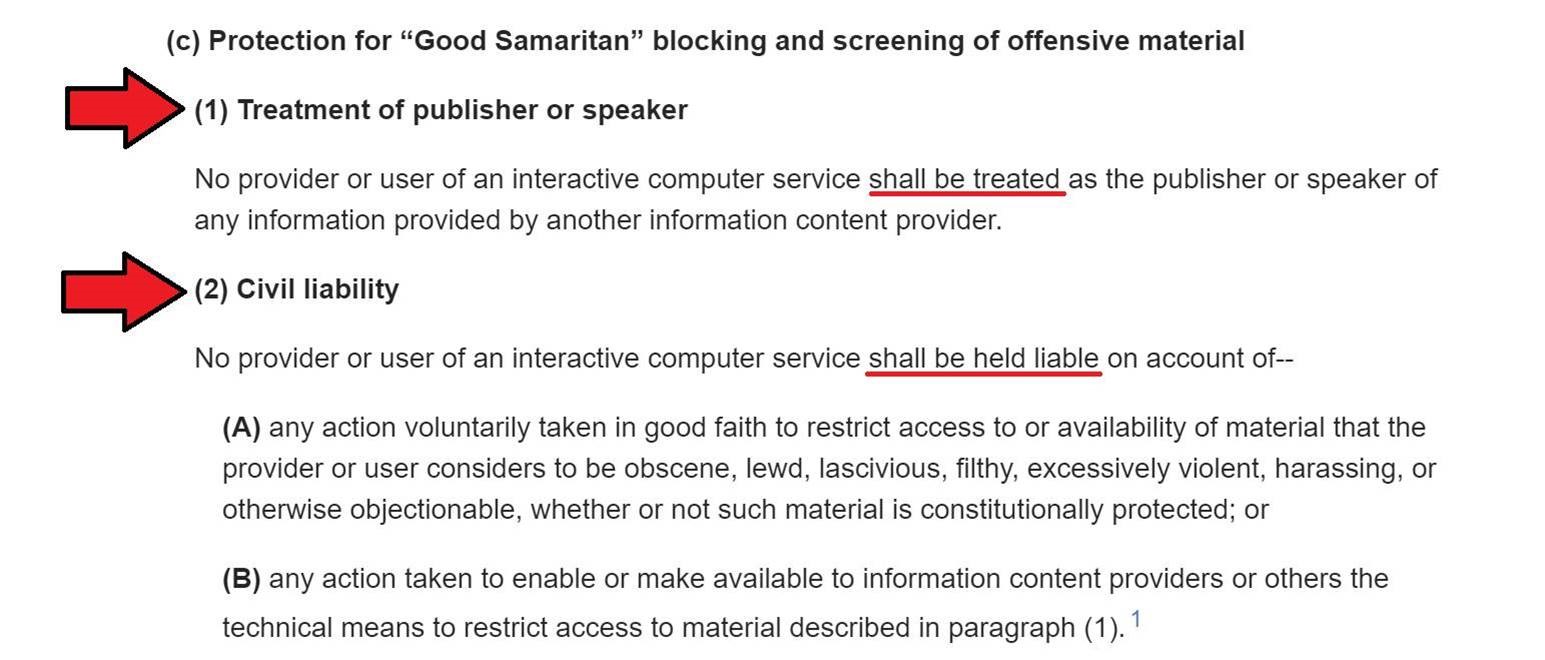

The complete CDA (47 U.S.C. § 230) is a long statute that contains several different parts. The main parts that matter for the purpose of this discussion are found in subsection (c) which is shown below. Note that subsection (c) contains two completely different parts: 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(1) and 47 U.S.C. § 230(c)(2). I have highlighted certain parts that I’ll discuss further in a minute.

Now, after looking at the statutory language, let’s summarize what these two different parts mean.

Part 1 (Section 230(c)(1)) says, in effect, that a website provider cannot “be treated as the publisher or speaker” of any information (content) provided by a user such as Ms. Bird.

Got that? The key rule established by Section 230(c)(1) is that you can’t treat a website provider as the publisher or speaker of someone else’s words. The key word here is “TREAT” – you can’t treat Person X as the publisher or speaker of something written by Person Y. Sorry; can’t do it because that would violate Section 230(c)(1).

TIME FOR A POP QUIZ:

Question – Do you see the word “liable” or “liability” anywhere in Section 230(c)(1) (this is an open-book test, so go back and look)?

Correct Answer – NO. The word liable does not appear anywhere in Section 230(c)(1).

Based on the plain language of Section 230(c)(1) (and more than 300 cases interpreting it), this much is CRYSTAL CLEAR: the rule established by Section 230(c)(1) is not limited to claims which try to hold a website owner “liable” or which impose liability for money damages. Instead, if a plaintiff is doing anything to treat a website operator as a “publisher or speaker” of someone else’s speech, then Section 230(c)(1) applies. It does not matter if the plaintiff is seeking money from the website owner or only from the original author. All that matters is that the plaintiff is trying to treat a website operator as the “publisher or speaker” of someone else’s speech. Section 230(c)(1) says YOU CAN’T DO THAT, STUPID!

So what about Section 230(c)(2)? Keep in mind – this is an entirely separate part of the CDA that creates a different rule. Again, I’ll paraphrase – under Section 230(c)(2), you can’t hold a website operator liable if it takes good faith steps to block or remove offensive content.

Do you see the difference? Blocking/removing content is not the same thing as posting or publishing content. Blocking content means taking stuff DOWN; publishing means putting stuff UP.

Section 230(c)(1) applies to claims that are based on a website operator’s decision to put something UP (i.e., publishing offensive speech)

Section 230(c)(2) applies to claims that are based on a website operator’s decision to take something DOWN (i.e., blocking or not publishing)

Why does this matter? Because — Section 230(c)(1) is actually much, much broader than Section 230(c)(2). Among other things, Section 230(c)(2) only applies to claims which are based on a website owner’s decision to block/remove content and in that situation, the website owner must show that it acted “in good faith” (this isn’t a big deal because how often is someone going to complain about a website refusing to publish something? Not very often, although it has been coming up recently; i.e., when conservatives claim their views are being “suppressed” on websites like Google and Facebook.)

Section 230(c)(1) is completely different. Under Section 230(c)(1), it does not matter if the website operator acted in “good faith” or bad faith. Unlike Section 230(c)(2), Section 230(c)(1) does not contain a good faith requirement, so the website operator’s good or bad intent is irrelevant. See Levitt v. Yelp!, Inc., 2011 WL 5079526 (N.D.Cal. Oct. 26, 2011) (explaining, unlike Section 230(c)(2) “§ 230(c)(1) contains no explicit exception for impermissible editorial motive … .”)

Under Section 230(c)(1), all that matters is whether the plaintiff is trying to treat the website operator as a publisher or speaker. If so, then the CDA applies…end of story.

That is exactly what happened in Hassell, and that is why Yelp won – because when Ms. Hassell asked the court to order Yelp to take content down, she was trying to treat Yelp as a publisher/speaker of content created by someone else (Bird). This is exactly what Section 230(c)(1) says you cannot do. IT’S THAT SIMPLE…and it has nothing to do with the separate question of whether Hassell was trying to hold Yelp liable (because remember – liability is only an issue under Section 230(c)(2), not 230(c)(1)).

That is why Yelp won in the California Supreme Court and why the U.S. Supreme Court refused to accept review. This result had nothing to do with the issue of whether Hassell was trying to hold Yelp liable or not; it was based on the clear and simple language of the CDA which does not permit the relief Ms. Hassell wanted.

FAIL #2—HASSELL IS AN “OUTLIER”; A “MINORITY INTERPRETATION OF THE ACT”

At the conclusion of his article, Mr. Heaphy tries to throw shade at the California Supreme Court, suggesting: “Although the U.S. Supreme Court denied review of the Hassel opinion, it is still a minority interpretation of the Act and companies seeking to protect their reputation can still seek orders requiring the removal of tortious online content, so long as they do so in a state other than California.” (emphasis added).

I’m sorry, but this is just completely false for at least two reasons.

First, Hassell does not represent a “minority” view of the CDA. To suggest otherwise is utterly false. On the contrary, in its decision, the California Supreme Court recognized and cited numerous decisions from other courts which all agreed that the CDA does not permit injunctive relief of the type sought by Ms. Hassell. Since Mr. Heaphy apparently missed this part of the case, I’ll quote it here:

The Court of Appeal recognized that other courts (e.g., Kathleen R. v. City of Livermore(2001) 87 Cal.App.4th 684 [104 Cal.Rptr.2d 772] (Kathleen R.); Noah v. AOL Time Warner Inc. (E.D.Va. 2003) 261 F.Supp.2d 532; Smith v. Intercosmos Media Group, Inc.(E.D.La., Dec. 17, 2002, No. 02-1964) 2002 WL 31844907; Medytox Solutions, Inc. v. Investorshub.com, Inc. (Fla.Dist.Ct.App. 2014) 152 So.3d 727) had construed section 230 immunity as extending to claims for injunctive relief.

And how many cases did the Hassell Court cite where injunctive relief was found to be properly available under the CDA? ZERO. NONE. NOT A SINGLE ONE.

To be completely fair, Mr. Heaphy says (correctly), that the California Supreme Court’s decision in Hassell only applies in California…and that’s completely true. No matter how hard it may try, the California Supreme Court can only establish law for courts in California, so its decision in Hassell is not binding in any of the 49 other states.

But this is a misleading point that leads to my second reason why Mr. Heaphy’s statement is inaccurate — although Hassell is not binding or controlling law outside of California, the CDA (a federal law) absolutely IS binding law in all 50 states. Of course, if a different state wanted to interpret the CDA differently than California did, it could certainly try….but does that mean it’s a good idea for people who want to remove online content to seek removal orders from courts outside California? Absolutely not.

The reason is pretty simple – let’s say you want to seek a removal order like the one Ms. Hassell got against Yelp. In California, these orders are illegal because they violate the CDA, so that is not an option. But, what about suing in a different state like Ohio?

It is true that the state courts of Ohio have never considered the same issue presented by Hassell, so it is technically accurate to say that it is possible the Ohio Supreme Court may disagree with California. It is possible that the Ohio state courts might conclude that the CDA does not bar injunctive relief against websites like Yelp.

NOTE – I personally litigated a CDA case – Jones v. Dirty World Ent. Recordings, LLC, 755 F.3d 398 (6th Cir. 2014) before the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals which is the federal appeals court that controls cases from Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio and Tennessee. As a federal appellate case interpreting federal law, Jones represents controlling law in Ohio and the other states in the Sixth Circuit. In the years since it was decided, Jones has been widely adopted by other courts, but it did not present the same issues as Hassell, and thus an Ohio state court could technically decline to follow Hassell if it wanted.

But here’s the thing – if that happened, it would mean that two different states have reached conflicting interpretations of the CDA. This would make it extremely likely that the U.S. Supreme Court would step in to decide which legal view was correct. Other than its refusal to grant review in Hassell, the U.S. Supreme Court has never taken a case involving Section 230(c)(1) or (c)(2)). If that happened, you can bet the case would draw overwhelming support from every website you can think of.

I personally think the U.S. Supreme Court would agree that Hassell was correctly decided, but either way, if you are trying to hide embarassing information on the Internet, taking your case up to the U.S. Supreme Court would be the best way to ensure the entire world gets to hear about your story.

CONCLUSION

I’m sorry this response is so long, but I want to end with this crucial point – criticizing the CDA is OK. Disagreeing with the legal ruling in Hassell is OK.

But what is NOT OK is for lawyers to trick clients into believing they have a magic bullet for removing embarrassing or offensive online speech when, in fact, they don’t. In many instances, filing a lawsuit to remove online content can backfire, causing the information to become even more widely spread (this is known as the “Streisand Effect”). This not only makes the situation worse, it ends up costing the client a fortune in legal fees in the process.

If you really believe you are being harmed by something posted online, you need to get good advice from an expert in this complicated area of law. Do NOT consult with your attorney-friend who only handles DUIs or bankruptcy cases. Instead, ask any lawyer you talk to how many cases they have personally handled involving the CDA, and ask them how those cases were resolved. Ask them for the case name/citation, and then use Google to check the result yourself. If the lawyer has never heard of the CDA or hasn’t handled a significant number of CDA cases, then you will probably want to look elsewhere for advice.

*NOTE REGARDING USE OF THE TERM “EXPERT”: Pursuant to ER 7.4 of the Arizona Rules of Professional Conduct, it is unethical for any lawyer to state or imply that they are a “specialist” in a specific field unless, among other things, the lawyer is actually certified in that field by the Arizona Board of Legal Specialization. Unfortunately, the Board does not offer certifications for “Internet Law” or the federal Communications Decency Act. Accordingly, my use of the term “CDA Expert” is not meant to reflect that I am a certified specialist in this area (I am not, since no such certification exists).

Rather, my expertise is based on the fact that I have personally litigated many dozens of CDA and CDA-related cases in both state and federal court including, but not limited to:

Lead Cases

Davidson v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, Case No. 1:18-cv-11394 (D.Mass 2019) (MTD pending)

Albert v. Ragland, 2018 WL 1163993 (Cal.App. 4th Dist. 2018)

Albert v. Hannah, 2018 WL 1163363 (Cal.App. 4th Dist. 2018)

Weinberg v. Dirty World, LLC, 2017 WL 5665023 (C.D.Cal. 2017)

General Steel Domestic Sales, LLC v. Chumley, 840 F.3d 1178 (10th Cir. 2016)

See also: General Steel Domestic Sales, LLC v. Chumley, 2015 WL 4911585 (D.Colo. Aug. 18, 2015)

Jones v. Dirty World Ent. Recordings, LLC, 755 F.3d 398 (6th Cir. 2014)

See also: Jones v. Dirty World Ent. Recordings, LLC, 965 F.Supp.2d 818 (E.D.Ky. Aug. 12, 2013)

Crabtree v. Dirty World, LLC, 2012 WL 3335284 (W.D.Mo. 2012)

Hare v. Richie, 2012 WL 3773116 (D.Md. 2012)

Dyer v. Dirty World, LLC, 2011 WL 2173900 (D.Ariz. 2011)

Gauck v. Karamian, 805 F.Supp.2d 495 (W.D.Tenn. 2011)

Asia Economic Institute, LLC v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, 2011 WL 2469822 (C.D.Cal. 2011)

See also: Asia Economic Institute, LLC v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, 2010 WL 4977054 (C.D.Cal. 2010)

Global Royalties, Ltd. v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, 544 F.Supp.2d 929 (D.Ariz. 2008)

See also: Global Royalties, Ltd. v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, 2007 WL 2949002 (D.Ariz. 2007)

Drafted Dispositive Pleadings For

Giordano v. Romeo, 76 So.3d 1100 (Fla. 3d Dist. 2011)

Blockowicz v. Williams, 630 F.3d 563 (7th Cir. 2010)

See also: Blockowicz v. Williams, 675 F.Supp.2d 912 (N.D.Ill. 2009)

GW Equity, LLC v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, 2009 WL 62173 (N.D.Tex. 2009)

Whitney Information Network, Inc. v. Xcentric Ventures, LLC, 2008 WL 450095 (M.D.Fla. 2008)

And many others…